Describing the Chassahowitzka must first begin with its name. Quite the mouthful, most locals pronounce it “chaz-a-whiskey” or fondly shorten it to “The Chaz”. Although not the first group of humans to encounter the springs and river of the Chaz, the Seminole Indians gave it the name it holds today.

Interestingly, the translation of the word has little bearing on today’s river. Chassahowitzka means “hanging pumpkin” in the Seminole language and likely refers to a variety of pumpkin native to Florida which grows from vines and was cultivated by the Indians. The pumpkin (commonly called the “Seminole pumpkin”) can still be planted and grown today, but is not found wild along the Chaz anymore. Hence, an outdated namesake that is wholly Native American and reminds us that we are but one generation of a long line of Floridians who have explored and enjoyed this river.

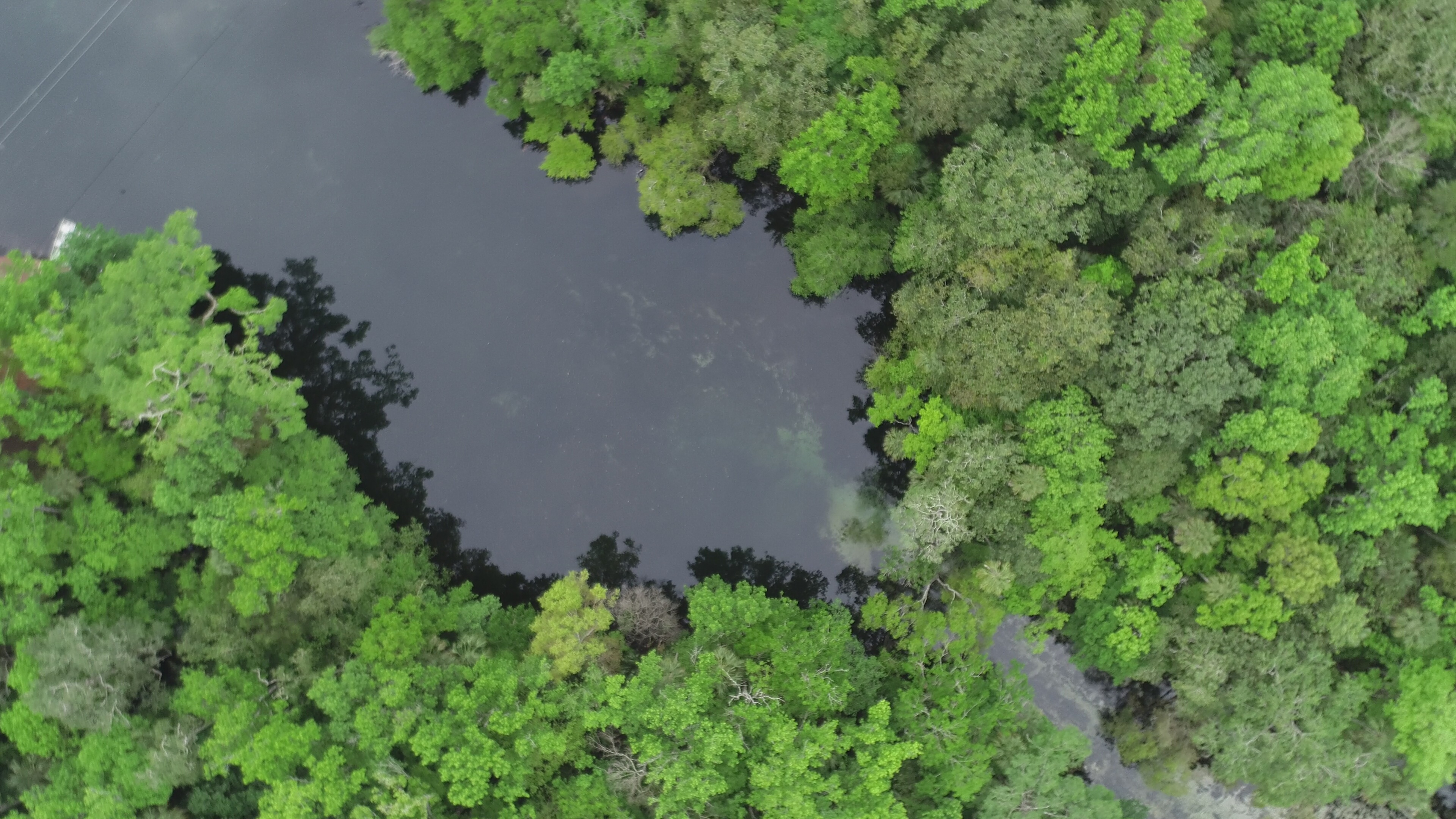

The story of the Chassahowitzka does not begin nor end with the Seminoles. A 2013 cleanup of the spring – which involved the removal of silt, algae, and other gunk which blocked the spring’s flow and was caused by effluent entering the watershed from septic tanks – revealed an interesting array of artifacts including a 10,000-year-old spearhead.

Aged to around the end of the last ice age, perhaps this weapon and its owner patrolled an area of different fauna and foliage than exists today, encountering a mammoth or alligator along the same route. Also discovered was a fish hook made of bone, a 2,000 year-old ceramic pot, and 17th century Spanish plate.

An informative article about the clean out and discoveries, with pictures, can be found here: https://www.cnn.com/2013/11/16/us/florida-spring-artifacts/index.html.

True or False: Birdwatching is an activity for older folks, extreme geeks, or those who love nature too much to shoot at it? All true, but it can also be an entertaining activity for the outdoorsman or woman who may only be able to identify six or seven types of birds, but who recognizes a good show when they see one.

Aves are strange little beasts. Badasses, really. How can it be possible that one species soars up above with the clouds, while the next dives below the water and swims with the fishes? On a quiet vessel like the kayak, you get the opportunity to observe these vocal beasts in true form.

In Florida, the best months to see the largest variety of waterfowl relying on the springs, rivers, and swamps are December, January, and February.

Cormorants are common along the Chass. Generally spotted with heads above water swimming along at a good clip, and then diving below to hunt.

On a recent outing, I observed one paddling towards a small creek inlet with a snowy egret along its bank and a great blue heron further down the creek. There must have been an old score to settle between these two beasts.

The cormorant swam to the bank and waddled right up to the egret, absolutely ripping into the egret with a great racket. The two birds squared up and yelled at each other for about thirty seconds, before the cormorant went off to dry itself. No blows were thrown, but it was clearly not a friendly meeting and quite interesting to watch for myself and the great blue.

Returning upstream, I observed a large osprey at the tip of a tree along the river bank. Continuing casually onward, I heard a huge splash behind my kayak – much too large to be a mullet jump and it scared the hell out of me, to be honest.

I turned to meet the swamp monster and saw the big white and brown osprey pulling itself up out of the water. Luckily, I would not be fighting any Chassahowitzka monster today. Talons empty, the osprey shimmied dry a few times midair before looping back and landing on the same perch. Obviously not fazed by the missed connection, but calmly prepared to strike again.

I paddled a little faster back to the head spring, in case the bird decided to come for me.

Leave a reply to Homosassa – First Magnitude Florida Cancel reply